1871-1902

Early years

At the École des Beaux-Arts, encouraged by his teacher Gustave Moreau to participate in public exhibitions, he began to make a name for himself. In 1894 he won the Prix Chenavard with L’Enfant Jésus parmi les docteurs(Infant Jesus among the Doctors), a work he would present the following year at the Salon des Artistes Français. He was 23 years old.

After his first participation in the Prix de Rome with Samson tournant la meule (Samson Turning the Millstone), Rouault was the favourite to win when he participated a second time in 1895 with Le Christ mort pleuré par les Saintes Femmes (The Dead Christ Mourned by the Holy Women). In the end, the academic painter Léon Bonnat disagreed and vetoed the award for Rouault.

However, these public exhibitions helped Rouault to make a name for himself. The socialist deputy Marcel Sembat, who would become a loyal collector, bought Le Christ mort pleuré par les Saintes Femmes, now kept at the Musée de Grenoble.

1902-1914

Rebellion

Deeply affected by his recent hardships, the death of Gustave Moreau and his solitude and sorrow, Rouault was “morally and physically exhausted”. Weak and exhausted, in 1902 he went to Evian for a period of convalescence. The peace and quiet and the beauty of the late autumn renewed his vision. He began paining with a new vigor.

During this period he forged new lifelong friendships with Léon Bloy and the philosophers Jacques and Raïssa Maritain. Inspired by Bloy’s ideas on society, Rouault reflected these in his painting (”Les Poulot”, characters from La femme pauvre [The Woman Who Was Poor] by Bloy). The Maritains would remain loyal supporters of Rouault’s work. Despite the unwavering friendship between Rouault and Bloy, Bloy rejected his paintings and would never understood them.

1914-1930

Solitary artist

Ambroise Vollard, one of the most prestigious art dealers in Paris, bought the full contents of Georges Rouault’s, a total of 770 works. The artist agreed on the condition that he could finish his work at his own pace. An amateur of deluxe books, Vollard commissioned Rouault with the illustrations of a number of books: Réincarnations du Père Ubu, Cirque de l’Étoile filante, Passion, Miserere and Les Fleurs du Mal.

For some ten years, between 1917 and 1926, his printmaking work was so intense he spent considerably less time on his paintings. From 1927, Rouault made an effort to finish hundreds of paintings to honour his contract with Vollard.

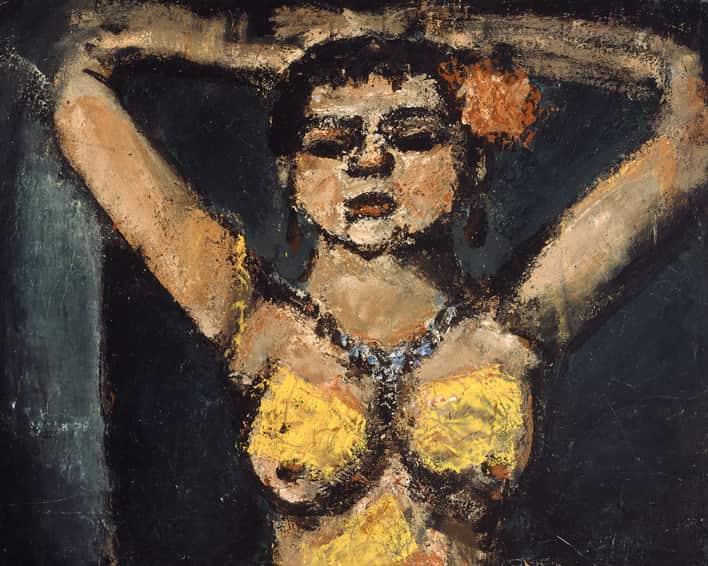

Most of his works represented circus figures, religious subjects or landscapes. In addition to these three major themes, he also painted nudes and portraits, gradually phasing out prostitutes, judges and grotesque figures.

1930-1948

Mature period

Rouault’s art became more controlled than in the 1920s, developing a peaceful and colourful grace throughout the thirties. His more static drawing and more brilliant palette expressed a spiritual harmony that would only intensify over time. His works celebrated the beauty of nature in flowers, landscapes and nudes and expressed a new decorative style using arabesques and borders.

In his sixties, Rouault enjoyed financial security and worldwide recognition. Reviews were abundant and unanimous. Although life for Rouault was more peaceful and stable, nevertheless he lived through another war and fought a bitter lawsuit with the heirs of Ambroise Vollard, who had died accidentally in 1939. In the solitude of his studio during the Second World War, he concentrated on experimenting with lines, shapes and colours and finished a large number of important works. More and more his paintings reflected a dreamlike inner world. The tragic realism of the Prostitutes and Judges gave way to more introverted and meditative figures. His paintings became increasingly spiritual and elevated.

1948-1958

Final symphony

The last ten years of Rouault’s career were characterised by an explosion of colour and an intensified use of texture. This final period is his most brilliant work and his crowning achievement.

The layers of thick paint are several centimetres thick in places. The black of the thick outline accentuates the uneven texture and creates light and shadow. The paint was treated with patience and persistence, slowly worked until it was transformed. Free from academic scruple, Rouault pushed his technique to the limit. The face of Sarah (1956) is a typical example of this period –an accumulation of layers of paint give the painting a sculptural aspect whist multiplying the shades, colours and light effects.