1930-1948 | Mature period

Worldwide recognition for his work

Rouault’s art became more controlled than in the 1920s, developing a peaceful and colourful grace throughout the thirties. His more static drawing and more brilliant palette expressed a spiritual harmony that would only intensify over time. His works celebrated the beauty of nature in flowers, landscapes and nudes and expressed a new decorative style using arabesques and borders.

In his sixties, Rouault enjoyed financial security and worldwide recognition. Reviews were abundant and unanimous. Although life for Rouault was more peaceful and stable, nevertheless he lived through another war and fought a bitter lawsuit with the heirs of Ambroise Vollard, who had died accidentally in 1939. In the solitude of his studio during the Second World War, he concentrated on experimenting with lines, shapes and colours and finished a number of important works. More and more his paintings reflected a dreamlike inner world. The tragic realism of his Prostitutes and Judges gave way to more introverted and meditative figures. His paintings became increasingly spiritual and elevated.

Themes repeatedly revisited

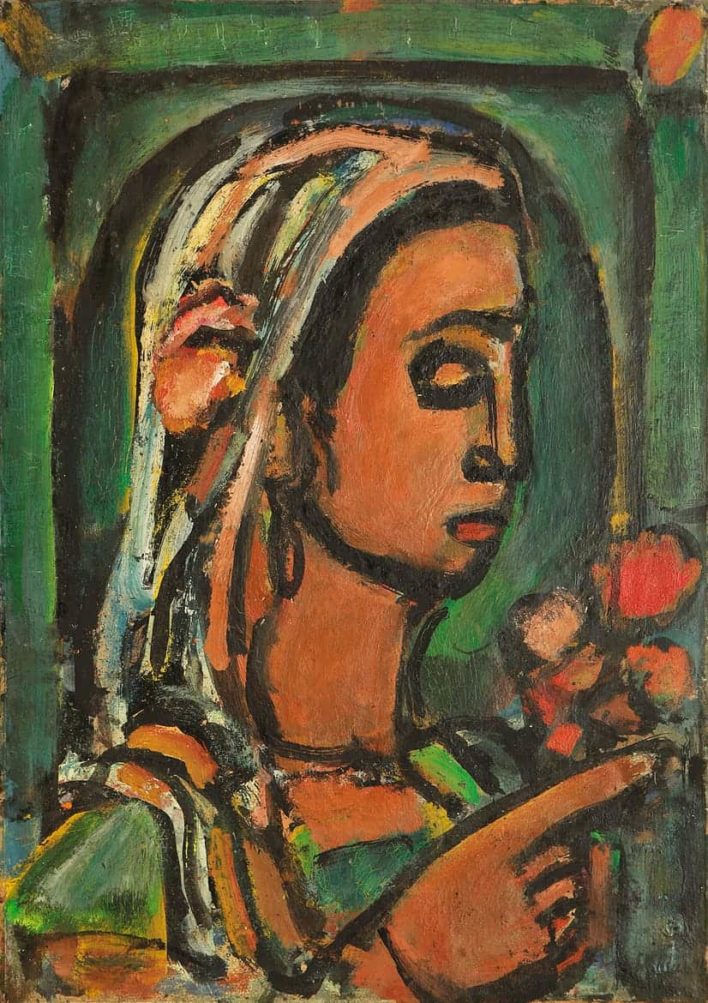

In his works of this period his themes included the circus and landscapes as well as series of imaginary and poetic faces, female nudes, still life and religious subjects. Rather than introducing more themes he would revisit his existing themes in new ways. The circus theme was dominated by this representation of the “Pierrots” who, like his clowns, depicted an enigmatic melancholy. Circus women, equestrian performers and dancers were given picturesque names such as Carlotta, Douce Amère and Carmencita. Sometimes we see intimate scenes of the family life of circus performers but most often these figures are solitary and placed in the foreground of the composition. A sense of silence emanates from these paintings. The tenderness of these mysterious and dreamlike figures contrasts with the pallid faces of the tragic clowns from his early period.

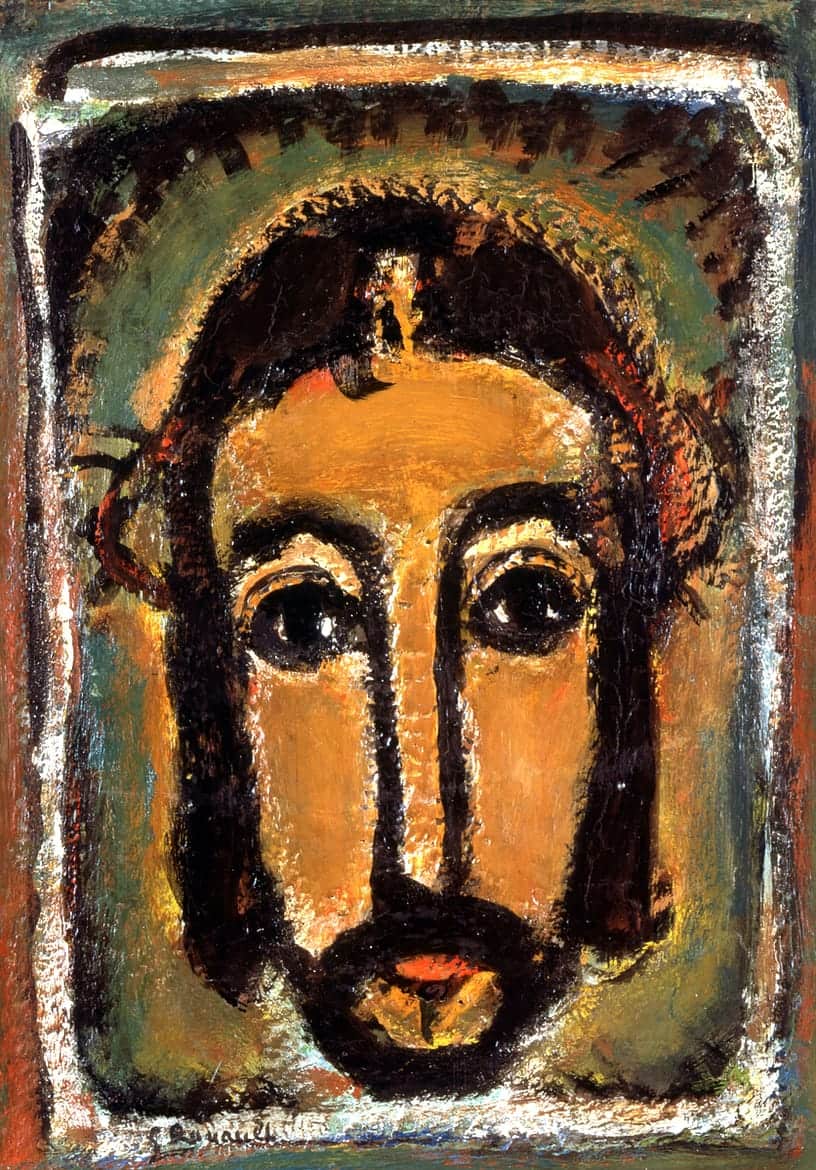

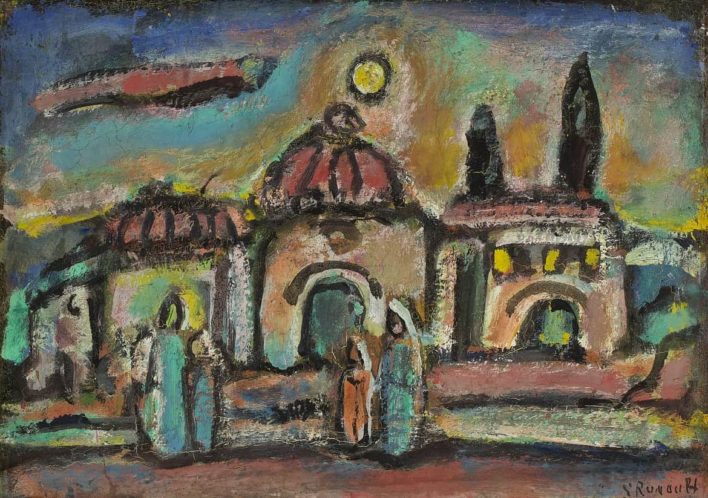

He created several series of religious works: Saintes Faces (faces of Christ) which evoke Byzantine and Roman iconography, heads of Christ, crucifixions and more and more religious landscapes. The painter called these landscapes “biblical” “mythical” or “Christian”. The miserable and cold landscapes of Ile de France, where nature is menacing, were gradually replaced between 1920 and 1930 by warmer colours and architecture inspired by the Orient. This was never real architecture, but was his own imaginary vision. From 1935, he painted nature in a more elevated style and the sun figured in many of his works. He painted figures dressed in tunics, without any other reference to traditional iconography other than the figure of Christ, who was continually present in these landscapes and gave a strong spiritual dimension.

Experiments with colour

In his landscapes, like in all his paintings, he achieved depth through his use of colour rather than through drawing. The infinite layers of paint brought a subtle transparency to the colours and allowed them to blend into each other. His palette continued to lighten and became very bright towards 1945-1947. Chrome yellows stood out against deep blues and dominated along with carmine reds and Veronese greens. Like a true alchemist, Rouault harnessed the intensity of the oil paints and their emotional power. The choice of colour was complemented by the contrasts between the cold and warm tones and this defined the expression of the painting.

Using this renewed colour palette, the artist experimented with techniques of paint application. The paint was thicker and applied in uneven layers. He worked the coloured paint into a paste in the manner of a craftsman. Under a low-angled light, the uneven surface looks like a geological structure with peaks and troughs. Between 1940 and 1948, the coloured paint became even thicker and richer, so much so that the works took on a three dimensional aspect. The colours were applied in large and consistent strokes. Rouault did not work on an easel. He placed his canvas flat on the table. Seen from above, the work could be touched, turned and turned again, like an object in the hands of a craftsman. This distinctive way of painting echoed the techniques he had acquired in ceramics and printmaking. In some of his later paintings, the paint looks like it had been fired in a kiln. The iridescent colours and transparency give them the appearance of ceramics or enamels. It gives the impression of a volcanic substance, solidified and multicoloured.

Simplification of form and drawing

With his printmaking, Rouault began a process of simplifying his form and his drawing. Around 1940, his forms become so pure, reduced only to the essential, that they become like signs, like symbolic geometric shapes. Rouault does not quite crossover into the figurative but often verges on the abstract. He remained a visionary painter who, throughout his career, would heed the advice of Moreau and listen to his inner voice.

You have studied the masters, you have followed them, and you have understood the great lesson which is to be yourself.

Letter to André Suarès from Georges Rouault