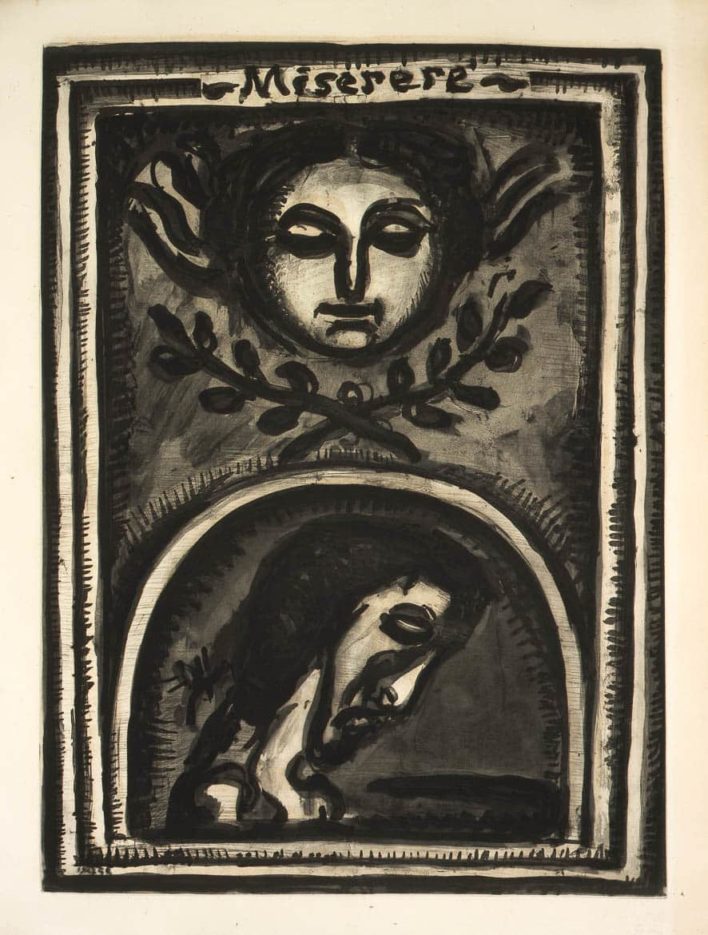

Miserere

Presentation by Frédéric Cherchève

(Grandson of Georges Rouault)

A little over a century ago, Rouault began a series of engravings on copper plates which thirty years later would be published under the title Miserere.

This monumental work, whose production was as long as it was painful, Rouault considered it as a representation of his artistic effort: “I was like a peasant in the field, attached to my pictorial soil, like the man hanged by his own hempen rope, like an ox under the yoke. Though terribly restless, I never took my nose out of my work save to ascertain the light, the shadow, the half-tint, the curious features of certain pilgrims’ faces. I noted forms, colours, fleeting harmonies until I was sure they were so indelibly impressed in my memory that they would stay with me beyond the grave.”

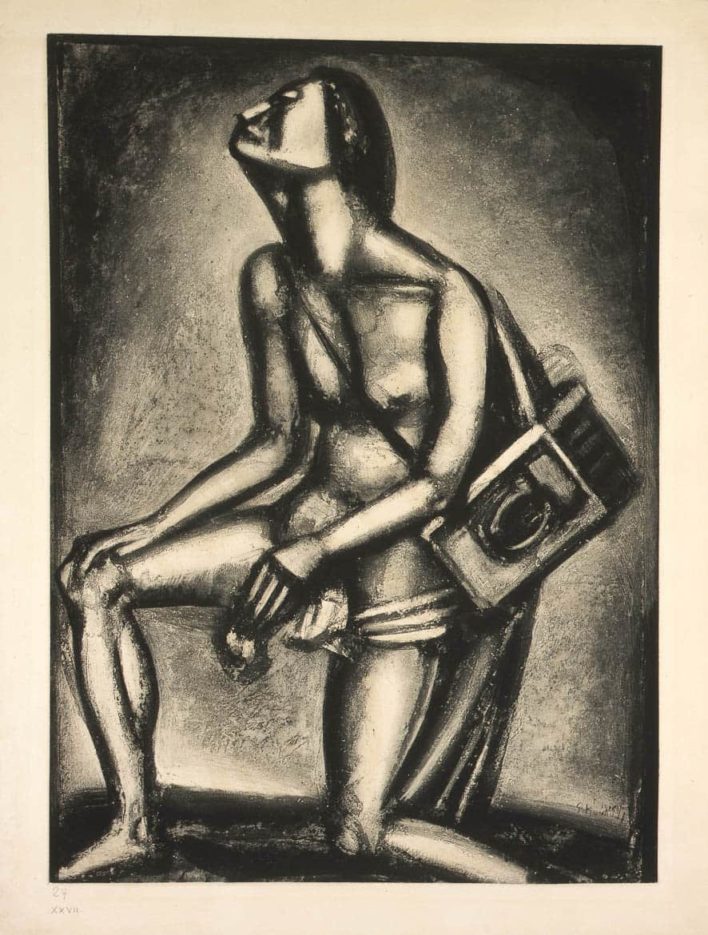

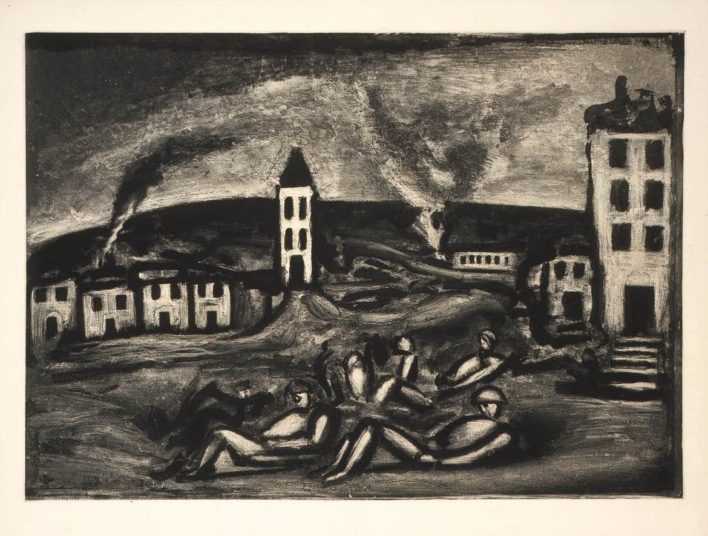

Inspired by the horrors of WWI, the work, initially entitled: Miserere et Guerre, went beyond the themes of this war and became, from its universality, a great panorama on the human condition.

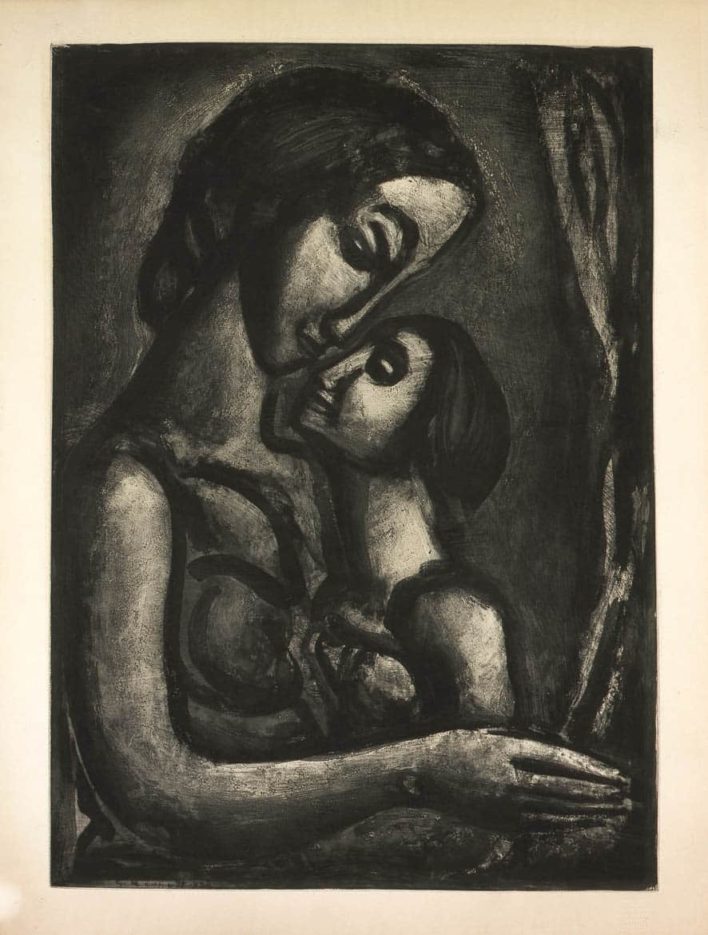

Misery, pain, sufferance and death are the eternal thoughts of man but faith gives them force and the light of Hope.

It is he who accepts to share this suffering for eternity that allows the artist to escape from despair and to wait for the Light to be reborn “Sing Matins, for a new day is born”

The shelter of the Cross, this is the only shelter favourable to the poor men who continue to carry in their heart a great love for what cannot be seen, nor weighed, and it is for them that I painted…

This is what makes this work – and all of the prints and paintings that came before or after – universal and timeless.

For a masterpiece of such considerable complexity, it was considered by its creator with great humility: “Do not speak of me except to speak of the art; do not consider me the torchbearer of revolt and negation, what I have done is nothing, do not hold me in such high regard. A cry in the night. A sob broken off. A strangled laugh Each day in the world, a thousand and one hardworking men and women, whose worth is more than my own, die from their effort.

Certainly, their death is perhaps worth much more than ours in the immense balance of God, but it does not leave a visible trace, Rouault is their cantor, their sculptor, their painter and the one who makes a lasting memory of them.”

The creation of the work

In the edition of Miserere published in 1991 by Le Léopard d’Or, Isabelle Rouault, the artist’s daughter, provides this insight:

“Georges Rouault wrote to Jacques Rivère in 1912: “It is following the death of my father that I made a series entitled Miserere in which I believe to have put the best of myself.” Thanks to this letter, found by the writer’s son, we can now be certain that Miserere was made even the war, between 1914 and 1948. These drawings in India ink to which the artist is referring were kept: on one of the first pages of a modest school notebook, the title Miserere written with a paintbrush. ”

The publication of Miserere

The 58 plates of the original edition were accompanied by captions written by the artist himself. Each print is the size of a canvas and the work weighs more than 21 kilos. Rouault wanted to make Miserere accessible to the larger public by publishing a small-format edition.

In her “Note for this new edition” Isabelle Rouault explains: “Following the original edition, my father was adamant that this new work, which he considered essential, was accessible to all and widely published in a smaller format. He took the effort to write the captions at the bottom of each subject himself so that they could also be reproduced in facsimile.”

Preface by Georges Rouault, 1948

“I dedicate this work to my master, Gustave Moreau, and to my valiant and beloved mother who with unstinting patience watched over and aided my early efforts when I wandered at the crossroads, an ill-equipped young pilgrim of art. Let me add that both, in their own way, were endowed with the same smiling and encouraging nature, seldom found in these times of bitterness and offense in which we seem to live today.

Most of the subjects date from 1914-1918. They were first executed in the form of drawings in India ink, and later transformed into paintings in at the request of Ambroise Vollard. He then had all the subjects transferred on to copper. It was desirable, apparently, that the copper should first receive the impression of my drawing. From that point on, I painstakingly tried to preserve the initial rhythm and draughtsmanship.

On each plate, more or less felicitously, without ceasing or pausing, I worked with different tools; there is no secret about my methods. Never satisfied, I resumed each subject endlessly, sometimes in as many as twelve or fifteen successive states; I should have liked them all to be of equal quality. I readily admit that I became attached to them, and that I was not insensitive to the desire of an American ambassador who wished to have some of the copper plates plated with gold and set in the wall at the embassy.

The impressions, which I carefully supervised, were completed in 1927, and later Ambroise Vollard had the plates cancelled.

After waiting twenty long years for their publication, which was delayed for various circumstances, I was fortunate enough to recover the engravings in 1947, and entrusted their publication to the Etoile Filante in Paris. It was planned that Andre Suares should write an accompanying text, unfortunately he was unable to do so.

The death of Ambroise Vollard, the war, the occupation and its consequences, and finally my lawsuit were all the causes of indefinite delay. Though ever hopeful, there have been dark times when I despaired that these engravings, to which I have always attached a great significance, would ever be published. I rejoice that this has come to pass before I vanish from this planet.

If injustice has been shown toward Ambroise Vollard, let us agree that he had taste and a passion for making beautiful books, regardless of time; but it would have taken three centuries to complete the various works and paintings with which, in utter disregard of earthly limitations, he wished to burden the pilgrim.

Form, color, harmony

Oasis or mirage

For the eyes, the heart, and the spirit

Toward the moving ocean of pictorial appeal

“Tomorrow will be beautiful,” said the shipwrecked man

Before he disappeared beneath the sullen horizon

Peace seems never to reign

Over this anguished world

Of shams and shadows

Jesus on the cross will tell you better than I

Jeanne in her brief and sublime replies at her trial

As well as other saints and martyrs

Obscure or consecrated

Paris 1948

Georges Rouault”